In a diary entry from October 1967, the British filmmaker Peter Whitehead described his assistant Anthony Stern as his ‘sole protector’ during the early stages of shooting The Fall in New York. Peter observes that, ‘Without his help in New York I’m sure I’d go crazy […] I would not function half so well without him.’ By that point, Anthony had been working as Peter’s assistant for three years, on projects ranging from promotional films for Top of the Pops and pop culture documentaries to collaborating as cameramen on other people’s productions. As roommates in Peter’s Soho apartment, Anthony and Peter lived and worked in close proximity: comrades in film production and personal witnesses to each other’s lives and loves. This intimate working relationship would stop abruptly—if indeed it ever truly stopped—when Anthony abandoned The Fall shoot and headed off for America’s West Coast to make his own film, the short psychedelic travelogue San Francisco (1968).

By the time Anthony left for San Francisco, he had already been involved in ten hours of rushes for The Fall. These were largely documentations of radical art performances and street protests, such as Rafael Montañez Ortiz’s brutal performance of Henny Penny Piano Destruction Concert (1967), and Penelope Tree and Buzz Miller’s Happening on the New York subway. Anthony also filmed sequences on his own, like the historic March on the Pentagon in October 1967, a mass anti-Vietnam war protest that took place when Peter was back in London. Sebastian Keep, a young filmmaker that Anthony and Peter had met at Tiles nightclub, was brought in to replace him, becoming responsible for shooting many of the sequences between Peter and Alberta Tiburzi and the Columbia University protest.

From its kinetic use of single-frame photography, and the presence of Pink Floyd’s “Interstellar Overdrive”, San Francisco is very much in conversation with both Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London (1967) and The Fall (1969). Coming out of Anthony’s experiences as Peter’s mentee and assistant on both productions, San Francisco nevertheless tells a very different story to The Fall, conceiving a romantic and perhaps more hopeful perspective on the utopian potentials of the hippie counterculture as 1967 drew to its close.

Becoming Peter Whitehead’s Assistant

Anthony first met Peter on the streets of Cambridge in 1964 as a young literature undergraduate dabbling in painting, poetry and music. Peter invited him to help on his first film, The Perception of Life (1964), an educational documentary on the history of the microscope funded by the Nuffield Foundation. Older, talented, handsome and charismatic, Peter was a unique figure that appeared to slip effortlessly and seductively between disciplines and mediums. He quickly became Anthony’s mentor, teaching him how to use various film cameras and sound recording equipment, and bringing him onto documentary and pop promo projects. This chance encounter with Peter would be a young man’s dazzling introduction to the world of filmmaking.

As Peter’s assistant, Anthony’s duties ranged from changing magazines, recording sound, shooting stills photography, and filming additional footage: some of which he shot with Peter, and some on his own. Peter paid him regularly—£12 a week in 1966, according to Anthony’s notebooks—to assist on anything that needed doing in the moment. Although Anthony was not the only cameraman to work with Peter (others included John Esam, David Larcher, Clive Tickner, and Sebastian Keep), he is probably the one that worked closest with him on the most projects during the Sixties. Anthony was assistant director on two of Peter’s 1960s documentaries, Charlie is My Darling (1966) and Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London. Together they shot footage for Théodora Olembert’s documentary Is Venice Sinking? (1968) and Pierre Roustang’s French documentary Les Teenagers (1969), all of which created exciting opportunities to travel to Italy, Sweden and France, filming motorcycle gangs, nightclubs and light festivals. They filmed footage for Richard Mordaunt’s Lusia Films and worked on some of the earliest British pop promos for Immediate Records, Andrew Loog Oldham and Tony Calder’s short-lived music label. These pioneering pop promos, made for musicians like P.P. Arnold, The Dubliners, The Beach Boys and The Rolling Stones well before the golden dawn of MTV, were intensely collaborative and demanded a quick turnaround. Peter filmed and edited, while Anthony recorded sound and shot stills. It was, as Anthony recently reflected, “an ideal system really, while it lasted…”.

With Charlie is My Darling, the first documentary on The Rolling Stones, Anthony left university to join Peter on the band’s 1965 tour of Ireland, documenting fans as they stormed the stage to meet their idols. In this year, he also started making his own films. Anthony’s first film, Baby Baby (1965), is a black-and-white Nouvelle Vague-inspired short that incorporates home movie footage of the birth of his first son Jeremy. Capturing the excitement and confusion of becoming a young father at only 21, it also experiments with speeding up and expanding cinematic time. By the time he made Iggy the Eskimo Girl (1966), a portrait of model and girlfriend Iggy Rose dancing barefoot in Russell Square, many of his ideas for formally representing psychedelic experience had begun to take root.  For Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London (1967), Anthony assisted Peter in tandem with John Esam, the New Zealand poet, filmmaker and LSD activist who had already worked with Peter on Wholly Communion (1965). Dashing around London with Peter, Anthony assisted on interviews with Julie Christie, Michael Caine, and Hugh Heffner; filmed dancers in low-lit and smoky nightclubs; experimented with light shows, and projected films onto The Move. Anthony also brought his own ideas to Tonite, like the use of lens exposures to produce painterly trails of neon light. And just like these neon trails, the boundaries of a collaboration as intimate as this one soon became blurred.

For Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London (1967), Anthony assisted Peter in tandem with John Esam, the New Zealand poet, filmmaker and LSD activist who had already worked with Peter on Wholly Communion (1965). Dashing around London with Peter, Anthony assisted on interviews with Julie Christie, Michael Caine, and Hugh Heffner; filmed dancers in low-lit and smoky nightclubs; experimented with light shows, and projected films onto The Move. Anthony also brought his own ideas to Tonite, like the use of lens exposures to produce painterly trails of neon light. And just like these neon trails, the boundaries of a collaboration as intimate as this one soon became blurred.

Peter would claim, in a 1967 interview on American television, that: “I am my own cameraman. When I make a film, I do all the filming myself.” Undoubtedly an excellent filmmaker, Peter clearly directed and edited the work alone, maintaining strong authorial control over his material. His roving verité camera was the expression of a singular viewpoint on events as they happened and, in the context of the interview, such a statement set him apart from the Hollywood studio productions that he so rallied against, bringing him closer in line with the stance of the auteur. Even so, one can see how notions of attribution—of who contributed what to the work—become fuzzy and fraught. If someone’s holding the camera, does this make the footage their work, ripe and ready for repurposing? If you’re exchanging ideas constantly—long, long, into the night—where do we draw the line between influence and creative credit? In the seemingly endless summers of the Sixties, notions of creative authorship and control were less important to certain forms of countercultural artmaking than the collaborative process of making the work, the act of being there to capture events as they happened, spontaneously and intuitively.

A Series of Moments Seeking a Synthesis…

The synergy between Peter and Anthony has interested me for some time. Both studied and lived in Cambridge. Anthony was born there in 1944 to middle-class parents working in academia and stayed in Cambridge to study English literature. Peter, meanwhile, was born in Liverpool to working-class parents, a plumber and a housewife, but won a scholarship to Cambridge as an organ scholar then switched to studying maths, physics, and chemistry. Both of them painted. Their canvases were exhibited, at different times, at the Lion & Lamb pub in the village of Milton.

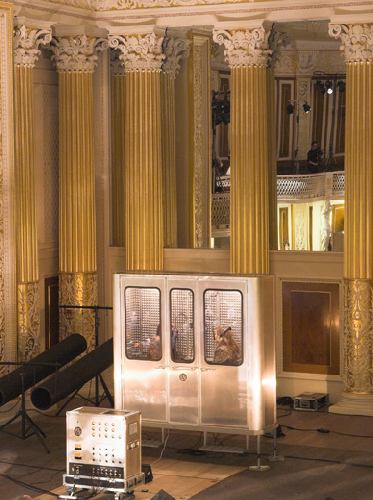

It was in this pub that Anthony and Roger “Syd” Barrett shared an exhibition of paintings in 1964. Once Anthony moved to London along with much of the Cambridge countercultural scene, Pink Floyd’s intrepid live performances at London’s psychedelic UFO Club entailed something of a group awakening. When “Interstellar Overdrive” briefly became the sound of the London counterculture, both Peter and Anthony used different recordings of the track in their own films. Peter paid to record Pink Floyd at Sound Techniques before they signed to EMI, using the music to soundtrack Tonite, and a black-and-white experimental short, Jeanetta Cochrane (1967). Meanwhile, Anthony later used a rare recording of the song given to him by manager Peter Jenner in San Francisco (1968). The song’s frenetic and improvisational glissando influenced Anthony’s disjunctive approach to editing—he claims to have edited San Francisco to the track on his return to London. Both filmed the band in full-length performances: Peter with Pink Floyd London ’66-’67, and Anthony, at a Pink Floyd sound rehearsal at the Queen Elizabeth Hall. They also dated and worked with Syd’s ex-girlfriends, Iggy Rose and Jenny Spires (Peter recently co-edited The Fall diaries with Jenny, almost fifty years after their brief relationship). Anthony’s impressionistic diary film Wheel (1969-71) was originally inspired by long conversations with Syd, who referred to Anthony’s Bolex camera as his “rose-tinted monocle.” In May 2009, Anthony, who remained a close friend of Syd throughout his life, co-organized a special homage to the singer at the Cinémathèque Française. Syd’s mercurial musical presence, and the sounds of Pink Floyd, unite these two filmmakers in interesting and complex ways.

The Fall (1969) and San Francisco (1968): Power and Beauty

With a bit of money given to him by theatre producers Iris Sawyer and Elinor Silverman, both of whom were backers on The Fall, Anthony travelled to the West Coast to make San Francisco. Then a Mecca for the hippie movement, Stern filmed San Francisco over several weeks, his roving camera capturing the energy of the city through gestural hand-held camera movement and dynamic single-frame animation. From protest marches to rock gigs, ecstatic dancing to hippie rituals shot at a San Francisco Mime Troupe apartment, it was documentation of the latter that prompted Films & Filming critic Ken Gay to wonder at the ‘strange hippy charade in which a nude girl is chief protagonist’, presuming it might be ‘amateur theatricals (but I may be wrong).’ Gay still acclaimed the ‘amazing colour kaleidoscope … distinguished by the pace of its flash frame editing and its freeze frame technique which is used to capture the frenzied activity of the city.’ Sunday Times critic Dily Powell described the film as a ‘stained-glass window on America’, inadvertently foreshadowing Anthony’s future career in glass. San Francisco was finished with the assistance of the BFI Production Board and won prizes at film festivals like Oberhausen, Melbourne and Sydney in 1969.

Peter Whitehead in Nothing to Do with Me (1969)

Peter Whitehead in Nothing to Do with Me (1969)

Back in London, Stern revived his working relationship with Peter on Nothing to do with Me (1969), a black-and-white, thirty-minute portrait of the filmmaker, shot in the period during which he was editing The Fall. Inspired by Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests and other more durational approaches to film portraiture, Anthony created the context for an “interview without questions.” He saw this approach as one that involved surrendering power to his filmic subject, opening space for the spontaneous flow of conversation and chance element. An exhausted Peter, no doubt weighed under by both the emotional fall-out from filming The Fall and the technical demands of editing his materials, begins to riff on the nature of consciousness, his experiences with mescaline, and the limitations of language to truly capture experience. Both behind and in front of the camera, the dynamic between the two had changed. By making San Francisco, Anthony had proved himself as an independent filmmaker, and turned the camera onto his mentor. The power dynamic between them had shifted.

After the Sixties, both filmmakers went their separate ways creatively, even though their personal relationship outlasted the decade, hitting moments of synthesis as well as rupture, true to the nature of collaborative male friendships. At different times, both artists would revisit their footage from the Sixties, reworking it in new and interesting ways. Peter did this with Fire in the Water (1976), and Anthony returned to his Sixties material following his Parkinson’s diagnosis. Get All that Ant? (2015) is Anthony’s feature-length autobiographical essay film of his time behind the camera. Anthony continued working as a cameraman well into the 1970s, working on concert and festival films such as Glastonbury Fayre (Nicolas Roeg and Peter Neal, 1971), and Yessongs (1973), Neal’s concert film on English prog rock group Yes; Anthony continued his collaboration with Peter Neil on the erotic collage film, Ain’t Misbehavin’ (1974).

And then, just like that, both Peter Whitehead and Anthony Stern abandoned filmmaking in a puff of smoke. Anthony turned to glass, and Peter to pottery. Naturally, that wasn’t the end of the story…

Sophia Satchell-Baeza, London 2020